Book lovers find more than solace in a book. They want to own the object of their desire and are quick to remember where they bought their first book. Buying a book for the first time is an experience mysteriously charged with emotion. Book lovers might harken back to that occasion with as much emotion as they would remember a first love. They will remember every nuance of their first encounter with a bookstore, from the sound of a cash register’s ring, to the slight crinkling noise of the book being stowed into a paper bag, and how the store looked in the late afternoon light with its thick shades rolled up or slightly tattered and fading, curling down. They recall the scent of new books with shiny, bright covers or old musty tomes with yellowed pages as conjuring as much emotion as the scent of their lovers’ hair. People who love books love them that much.

People who love books feel very much at home in community bookstores. Independent “indie” bookstores transcend the book buying experience beyond being a financial transaction by giving people a place to experience books. In this way, indie bookstores are crucial for creating community around books. The number of indie bookstores in a town or city often mirrors the demographics of a culture. For example, the city of Yonkers, where I grew up, borders the Bronx and is the third most populous city in New York State; yet, it only has one bookstore, a Barnes &Noble, which is hardly an indie. The complete absence of indie bookstores might be a reflection of the city’s roots in a working-class culture. Whereas cities like Boston, San Francisco and Seattle have many indie bookstores, which could be a reflection of their highly educated populations.

There was a time during my childhood when my hometown Yonkers did have indie bookstores. The Alicat Bookshop on 287 South Broadway in Yonkers was my first love. Books overflowed on tables and were piled high to the ceilings, so much taller than I could reach at age ten. The store smelled as musty as a pair of my grandfather’s old leather boots, finely crafted but cracking at the seams. I held a paperback classic in my hand, flipped the tattered pages, and for the first time in my life I made a book mine for a quarter. I owned this book and it became part of me. It took years before I could fully appreciate the French novel Nana. Emile Zola was a little over my head, but even then I longed to reach higher than my hands could grasp.

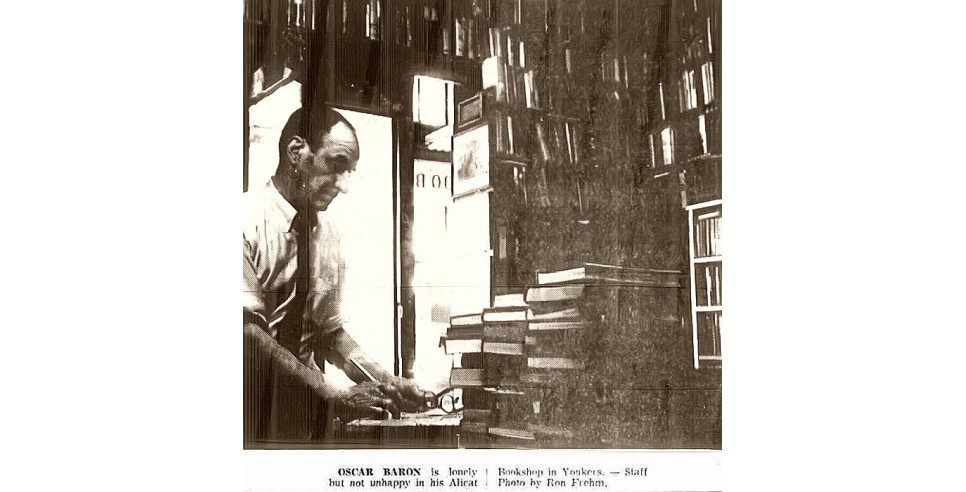

The Alicat was legendary in the book world. The bookshop had actually expanded into a small press, publishing a series of chapbooks with a limited print run of 750 copies that were each sold for a dollar. Alicat’s owners, Oscar and Florenz Baron, claimed to have been the first to publish Henry Miller’s works that had originally been banned in America. The Barons considered themselves to be moderately radical lefties who hobnobbed with the literary likes of Anais Nin, Dorothy Parker, William Carlos Williams and James Baldwin. But as a kid I didn’t know that. I did know that they sold brown-paper-wrapped mystery packages of eight or ten old books for a quarter. Buy, trade or sell, you could return two books for a new one. Due to a lease dispute with their landlord, the Alicat shut its doors in 1974. Oscar Baron died two years later, but Florenz Baron continued to sell books from her home on Ludlow Street in Yonkers well into the 1980s.