Why is rap singing or city council voting heroic? In contrast, imagine working for nearly forty years in an industry where you knew from the get-go that the odds were stacked against you climbing to the top of the chart because of your gender. If this is difficult, imagine climbing Mount Everest for forty years, and failing to reach the top every time. This has been the conundrum for all women in publishing since the first women were allowed in. The first American female publisher was Elizabeth Timothy, who worked with Benjamin Franklin to take over her husband’s newspaper, South Carolina Gazette, back in 1739. The Ivy League university press ceiling was broken three years ago, in 2014, by Jennifer Crewe, the Associate Provost and Director of Columbia University Press (CUP). I asked Crewe if this achievement has meant a statue in her honor: “I assume you are joking about the statue,” she replied. There is no Wikipedia page to salute her achievement.

“There isn’t much popular appreciation for the kind of books we do,” she added. No appreciation for the industry that vets the work of top professors in the country? Education is one of the top expenses and causes for life-long indebtedness in the US, and yet, the directors and editors who chaperone the people selling knowledge are working “in the background.”

Crewe’s particular achievement can be clarified with some additional statistics. The Ivy League consists of only a handful of universities with presses. The other university presses broke this record earlier. The first major corporation, Coca-Cola, saw a female director in 1934, Lettie Pate Whitehead (and she was primarily a philanthropist). According to a Publishers Weekly survey, “85% of publishing employees with less than three years of experience are women.” The survey also discovered that in this sector, in 2010, “women make on average $64,600 compared to men, $105,130”.

A large number of these women survive the first years, and make up the majority of the publishing industry at all levels, with the exception of the top spots. These types of inequalities would probably discourage most women from joining the publishing industry, but the numbers are hidden beneath the cloak of “researchers” that claim that we live in a post-feminist society, where no sex-based discrimination exists, and women should be happy they can find a job, even if it pays 60 cents on the dollar. In this environment, it is inspiring to see that, finally, in 2014, a woman has managed to secure a directorship of an Ivy League press. So, let’s take a look at how she did it, so we can all learn how to follow her example.

Crewe’s upbringing explains the type of roots it takes to survive the publishing ascent: “My father was a physicist at the University of Chicago and my mother was a teacher before she had me. She was a school board member of every public school I attended after we moved to a suburban area, and she served on the State of Illinois School Board.”

After finishing a BA at Sarah Lawrence College, she began an MFA at Columbia University. “I was lucky in that the University of Chicago provided a tuition benefit for children of faculty, so my tuition in college was covered. I received a scholarship from Columbia, but needed to earn money so I worked part-time at Columbia University Press while I was working on my MFA. I had refused to learn how to type while I was in high school because I didn’t want to end up as a secretary. But after college I realized it would be more efficient to type properly, and I knew that in order to get an entry-level job I would need that skill. My first job at Columbia was re-typing, very slowly, on an IBM Selectric, letters that my boss, the then-humanities editor, had typed at 100 wpm on a manual typewriter and then edited.”

Publishing had become a more sensible choice than poetry for a career: “I started out wanting to be a poet. I had some poems published, won the 92nd St. YM-YWHA Younger Poets award, and a publisher showed some interest in my manuscript. But I was not confident enough to ask more established poets to push my cause and help me publish the book. I needed a steady job and wanted to stay in New York, and I didn’t feel comfortable taking adjunct positions that were not secure. So eventually my publishing career took precedence over poetry.”

A year into her MFA, she became an Editorial Assistant at CUP, remaining there and gradually moving up the ranks to Manuscript Editor from 1978 through 1982. She wanted to move away from copyediting and into acquisitions work, so she moved to Charles Scribner’s Sons as editor, keeping that same job without advancement through 1986, when she returned to CUP, and remained there ever since. When asked about sex-based discrimination in publishing, Crewe explains: “Soon after I was hired at Macmillan in the mid-eighties I learned about a class action suit brought by female employees, and that my salary was $5000 less than that of male colleagues doing the same job. My salary was increased because of the efforts of women who came before me. Now that kind of blatant wage discrimination doesn’t happen often, but subtler forms of discrimination against women continue.” A look at publicly available academic salaries for men and women at most colleges still show at least an 8:10 ratio salary discrepancy, but it is motivating to know that fair wages are possible only if all women sue their employers. Scribners, now a division of Macmillan, saw its first female publisher in 1985, Mildred Marmur, just as the $5,000 discrimination lawsuit was wrapped up, and just before Crewe decided to leave Macmillan for CUP.

Akeel Bilgrami, Sidney Morgenbesser Professor of Philosophy, Wael Hallaq, Avalon Foundation Professor in the Humanities and the author of The Impossible State, which won the first prize at this event, Jennifer Crewe, and John Coatsworth, CU Provost

Crewe started in an acquisitions editor position back at CUP as Executive Editor (1986-90). She was later promoted to Senior Executive Editor (1990-94), then to Publisher for the Humanities, a managerial position (1994-99), then to Editorial Director (1999-2005), then to Associate Director and Editorial Director (2005-13), before becoming the Interim Director (2013-14), and then President and Director (2014-15), and finally Associate Provost and Director (2016-). This is an example of a very steady and determined climb. The length of this struggle begs the question how Crewe managed to keep from leaving CUP for a non-Ivy press, where she might have become a director decades earlier: “I was offered a directorship at a non-Ivy press just before I received the Columbia offer. I would certainly have left Columbia if I hadn’t received the offer to become its director.” I had worked hard, knew how I would lead the organization, and I would not have wanted to stay under another director.”

Women’s willingness to take lower salaries and to remain despite serious underpayment is both the reason there are so many women in publishing, and why they’re paid up to half less than men.

It is typical for universities to require some service to the field, but Crewe explains that “during the years I was frustrated about ever becoming director of the Press, I threw myself into the service work as an outlet.” She has participated in a number of major academic associations. Her most recent, crowning achievement was an election, in June of this year, to the President-elect position of the Association of American University Presses. Her presidency will begin in June 2018 and will run for a year. She has also served on the Executive Council of the Association of American Publishers Professional Scholarly Publishers division, the Modern Language Association’s Executive Council, and various smaller committee roles earlier in her career. She received several awards, such as the AAUP 2006 Constituency Award, and, most recently, she was named to the rank of Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Minister of Culture. She has also given talks on scholarly publishing at the MLA, Association for Asian Studies, Society for Cinema and Media Studies, AAUP, PSP, and at international conferences. She has published essays on cinema, Asian studies, scholarly publishing, and dissertation revision.

She continued her formal education in 2003, with the University of Chicago’s Graham School “Economics of Small Press Publishing” course. Christie Henry was working for the University of Chicago Press at this point, but they met later on the German Book Office Scholarly Editors’ Trip to Berlin and Munich, in 2010. Then in 2013, Crewe took the Yale University “Leadership Strategies in Book Publishing” course.

Crewe Speaking with Christie Henry at an AAUP Reception

To confirm the answers that Crewe gave in this interview, I also contacted the second woman to become an Ivy League press director, Christie Henry, who has just been appointed to serve Princeton University Press. Henry took the same Yale Publishing course as Crewe, two years later in 2015. This was not a coincidence: “Jennifer had recommended it to me, and I know well to take Jennifer’s advice—she is an incredibly inspiring publisher.”

Few male university press directors have similar credentials to Crewe’s, so why did it take women three hundred years of work in publishing to break the ceiling of first Ivy League university press director in 2014? The length of time women have waited for this news depends on the terms used. If the words are given loose definitions, the first press founded in America was an Ivy League university press, and it was directed by a woman. Upon Reverend Joseph Glover’s death in 1638, his widow, Mrs. Glover, took over a press he imported into the New World in 1638. She then married Henry Dunster, the president of Harvard College, who took the press under Harvard’s umbrella. Mrs. Glover was British by origin, and this is why the record of first American publisher goes to Elizabeth Timothy in 1739. Women have been involved in publishing since nearly the creation of the printing press, so women’s rights in publishing have regressed since the 1600s and 1700s, until this past decade when women have retaken more leading positions. Corporate culture contributed to the suppression of women in publishing, whereas they were freer to ascend in the days of small independent presses, as I explain in the book I am currently finalizing on the history of author-publishers.

Crewe’s predecessor at CUP, James D. Jordan, became the President and Director of CUP with 31 years of publishing experience, while Crewe received the job with 36. Before his CUP appointment, Jordan started serving as the Director of The Johns Hopkins University Press in 1998, only 20 years into his career. Henry faired a bit better at Chicago. Henry’s predecessor, Peter J. Dougherty, became the Director of Princeton University Press with 33 years of publishing experience, while Henry got the job with only 24 years at the University of Chicago Press. So, it seems there has been progress in the decade between the start of Crewe’s and Henry’s careers. Given these statistics, I asked Crewe if she has seen evidence of unfairness in promotions even as she was steadily climbing up the ladder. “I was the ‘inside’ candidate when Jim Jordan was hired. For various reasons I think the committee felt that someone from outside the Press was needed to run it at that time. That said, there still exists an ‘old boy’ network, and women have a more difficult time getting promoted or placed into top positions. That was certainly a factor in the decision about the three directors at the Press before me. On the other hand, I felt better prepared and more confident about what needed to be done once I did get the job.” Well, no male director could have been humble enough to see a lack of earlier promotion as a cause for celebration. Women’s stereotypically cooperative and peace-making nature is the reason they make great leaders, but this lack of power-hungry aggression might be what men in publishing have been using to keep them from advancing.

When asked about how sexism festers in publishing, Crewe explained: “Women are in lower-level jobs and middle management in publishing and, until recently, rarely at the top. Now we have 57 women directors out of 143 university press directors.” These are better odds than a few decades ago, but the male sex still has double-chances. The chances are much better at CUP, as in addition to having a female director: “We are very careful at CUP to compensate employees equitably. Our staff of 59 people includes 30 women and 29 men.”

Thinking about inequality can be discouraging, so I asked if it might be better for women in publishing to just focus on doing a great job: “Women should focus on working around the obstacles they face, drawing attention to sexism and misogynistic behavior in the workplace, which is often unconscious, and taking every opportunity to show what they are capable of, to voice their ideas as much as men do, and to demonstrate their ambition to move up.”

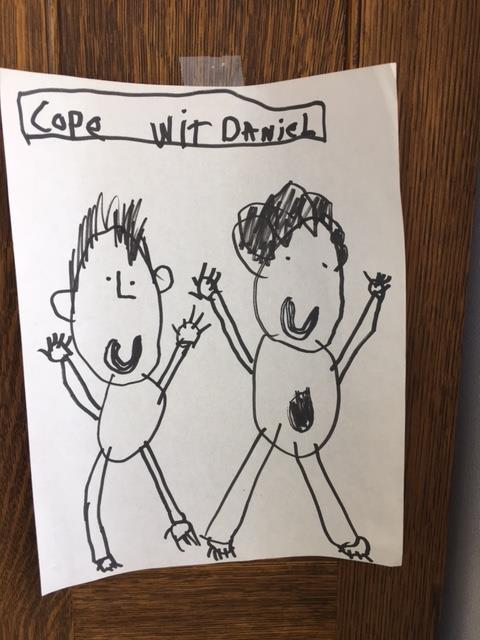

The most common excuse male researchers offer for women’s lack of upward mobility is that they’re too distracted by raising a family, so I asked how Crewe managed this aspect. “I married someone I met during college, and we have two boys, ages 27 and 23. I have a drawing taped to the side of my office bookshelf that no one else can see. It was made by my now 23-year-old son when he was about 6. I had handed him a black magic marker and a stack of paper to amuse himself while I was in the office on the weekend trying to get some work done. The drawing is of two figures—me and him, and at the top, in a rectangular box, are the words ‘Cope wit Daniel.’ Clearly there were times I couldn’t be with my family because of my job, but I think it was good for my children to see my progression through my career. I was lucky that during the time my children were young my office was only a few blocks from home. Women who have long commutes have more trouble. I take the subway to work. Work/life balance remains difficult for women because they still do the lion’s share of the housekeeping and child rearing.” For anybody speculating what happened to Daniel since he drew his masterpiece: “He has graduated from Sarah Lawrence and is planning to go to graduate school for classical guitar and music composition.” Meanwhile, one of the specializations Crewe lists on her CUP profile is food studies. When asked if she thinks cooking or food science is stereotypically women’s work, she replied: “The food list I developed here has nothing to do with my gender—my husband is the cook in our family. In 1999, I published a translation of an annales school European social history of food, and discovered there was a strong, interdisciplinary audience for serious books on food history and science, so I developed a list.”

Drawing by Daniel Conant

Crewe has contributed to women’s rights in publishing via her service. The top article that comes up on Google for female university professors is about Crewe from Sal Robinson. She mentions AAUP’s WISP group (Women in Scholarly Publishing), saying that it has “faded” since its heyday. The article does not specify if Crewe was active in WISP, so I asked for clarification: “I did participate in WISP—it was a good early effort at supporting women in the business and developing a community. In the years that have passed since that group was started women are represented in far greater numbers in university press publishing.” This is indicative of the way that women who join organizations like WISP climb higher than women who assume that women already have all the rights they need.

Both Crewe and Henry are involved in other feminist activities. As Henry commented: “Chicago has a wonderful organization, Chicago Women in Publishing, that is our local version of WISP. I would like to explore the causes of the fading of WISP, and also think about how to approach professional development and networking in other ways.”

Crewe and Henry mentioned actively participating in the Women’s March. Crewe specified there was an urgency to act “after Trump’s inauguration.” Henry described the event: “One of the most profound experiences for me was marching with my daughter this year—for the Women’s march and also for the March for Science—the latter of which the UC Press marched in as a group, after an incredibly creative sign-making festival. I think living by doing, and modeling by doing, are essential. My daughter shares my pride in being the first female director at PUP, but her first question on hearing that news was, ‘why did it take them so long?’”

“Henry was a Peace Corps baby, born in Cote d’Ivoire. My parents were both educators. I met my husband at Dartmouth, and followed him to Chicago, where he pursued a PhD in anthropology.” She started working for the University of Chicago Press. Their kids, Ellie (13) and Jack (11), attended the University of Chicago Lab schools.

Recently we have seen the closing of a few small university presses, including Rice University Press, Iowa State University Press, and most recently, Duquesne University Press. Ivy League presses have not suffered a loss yet. As Scott Sherman wrote in his The Nation article: “Most presses receive annual subsidies that tend to range from $150,000 to $500,000, while a handful of presses, such as Yale, Princeton and Harvard, enjoy the feathery cushion of an endowment”.

Since 1999 at CUP, Crewe: “Managed my own $2.6 million list with front-list sales of $1.2 million.” In an article about Crewe in Self Awareness, Columbia’s Provost, John H. Coatsworth commented that one of the reasons she was chosen was because she “negotiated an agreement for the Press to distribute Woodrow Wilson Center books” during her interim appointment. The interim post was a frustrating spot for Crewe as the university delayed the hire, despite Crewe having taken “the position knowing that I was going to be a candidate for the permanent job.”

Crewe explained the philosophy that has kept her and CUP at the top amidst devastation at some other presses: “American university presses are not-for-profit organizations. But we are also not-for-loss. The University gives us a subsidy equivalent to 8.5% of our operating budget. The rest must come from sales. The University also covers a portion of our rent.” The Nation article did not specify that CUP was among the cushioned Ivy Leaguers. And indeed, Crewe clarified that: “CUP does not have an endowment.” This lack has meant that CUP is “the smallest of the Ivy presses,” which has “managed to succeed even without the help of an endowment.” The main job of the director is to juggle the balance between the need for sales revenue and the need to publish high quality scholarship. As Henry puts it, university presses are, “trying to make the world a smarter place.” Crewe elaborated on this juggling act: “The most stressful thing is worrying about whether we can make our sales budget every year. As with other businesses we are at the mercy of market forces and it’s difficult to sell enough copies of many books to earn back our costs. So, we are beginning a fund-raising program and we are publishing more course adoption books and general interest books that do better than break-even.”

One of the distinctions between CUP and the other Ivy League presses is that, according to Crewe, up until January 2016, it was “a separately incorporated not-for-profit company. I was very pleased about our move into the University—indeed, I requested it—as it brought us closer intellectually to the university and it was beneficial to our staff in myriad practical ways. When we were integrated and became a unit of Columbia University, under the office of the Provost, I was given the title change to Associate Provost and Director. This title clearly signaled to the community how integrated we had become.”

As a non-profit, CUP actively courted distribution, fundraising and other opportunities that other Ivy League presses did not need to pursue. The need for a strong director that made a positive difference probably made CUP the type of environment where the first female Ivy League director could flourish.

Upon reviewing the statistics from the Publishers Weekly story above, Christie Henry commented: “These numbers are really discouraging, and I aspire to be a disrupter to these statistics. And at this salary differential, those women who opt to engage in family life and parenting, the decision has to be made about whether to spend an entire paycheck on daycare. We, as a community, face the same sort of responsibilities that most industries face in terms of retention through the parenting years, but I have also long appreciated the flexibility and adaptive nature of the publishing world, particularly the university press world. And I am hopeful we can see more growth in the ranks of female managers.”

The mere survival of scholarly publishing in the anti-intellectual climate in America today is heroic. Surviving and thriving in Ivy League presses is harder to attain than an Olympic medal. There have been nearly 30,000 Olympic medals awarded and only 2 female Ivy League press directors across world history. With odds like this, somebody should be singing something about the great work women like Jennifer Crewe are doing for the rest of womankind