Oringinally Published: (Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 11:1 2012, pp. 191-216)

Many Americans were outraged when the Wall Street banks paid out an estimated $18.4 billion in executive and staff bonuses in 2009, even while the economy was being cratered by the financial meltdown and the Great Recession.1 It seemed very unfair; the perpetrators were being rewarded while the victims were paying a terrible price.

Indeed, the stock market crash and the loss of home values in the subprime mortgage fiasco reduced the total net worth of American families by $12.3 trillion (about 30 percent), while 8.8 million workers lost their jobs and $700 billion in taxpayer money was appropriated to rescue the banks.2 The widespread perception that the bankers had avoided the consequences of their actions (“moral hazard” is the textbook term for it) helped to fuel the Occupy Wall Street movement that erupted last year.

Among other things, this notorious episode demonstrates that fairness is not just a philosophical construct, or a legal principle. It is a “gut issue” that pervades our social, economic and political life. We now know that a sense of fairness is a deeply rooted aspect of human psychology and a battleground where many of our political conflicts are fought. Indeed, fairness has emerged as a central issue in the 2012 election. President Obama invoked variations on the term “fairness” no less than 14 times in his important Osawatomie speech at the end of 2011.3

However, the underlying reason for the public distress about fairness goes far beyond Wall Street bonuses. This infamous incident was only a symptom of much deeper problems with our capitalist economic system, including the extreme concentration of wealth, the ever-widening gap between the super-rich and the rest of us, and especially the spreading sea of poverty (or near poverty) that now afflicts about one-third of our population.4 A growing number of Americans feel that our economy is fundamentally unfair.

In my 2011 book, The Fair Society,5 I argue that the implicit “social contract” that binds together any reasonably stable and harmonious society is breaking down in this country, with ominous potential consequences, and that it is time to re-define fairness and re-write the social contract in a way that puts fairness first. Here I will provide a synopsis of this argument and will outline some of the implications for public policy.

II. The Science of Human Nature

Some cynics view fairness as nothing more than a mask for self-interest. As the playwright George Bernard Shaw put it, “The golden rule is that there is no golden rule.” But the cynics are wrong. One of the important findings of the emerging, multi-disciplinary science of human nature is that humans do, indeed, have an innate sense of fairness. We regularly display a concern for others’ interests as well as our own, and we even show a willingness to punish perceived acts of unfairness.

The accumulating evidence for this distinctive human trait, which spans a dozen different scientific disciplines, suggests that our sense of fairness has played an important role in our evolution as a species. It served to facilitate and lubricate the close-knit social organization that was a key to our success as a species. This evidence is reviewed in some detail in my book. Here is a very brief summary.

In the field of behavior genetics, many studies have documented that there is a genetic basis for traits that are strongly associated with fairness, including altruism, empathy and nurturance.6 In the brain sciences, the experiments of Joshua Greene and his colleagues identified specific brain areas associated with making moral choices.7 Another team, headed by Alan Sanfey, pinpointed a brain area specifically associated with feelings of fairness and unfairness when subjects were participating in the so-called “ultimatum game” in his laboratory.8

Yet another source of evidence involves the biochemistry of the brain. In a series of laboratory experiments, neuroeconomist Paul Zak and his colleagues have demonstrated that a uniquely mammalian brain chemical, oxytocin, is strongly associated with acts of giving and reciprocating. Indeed, artificial enhancement of oxytocin levels in the brain can augment these behavioral effects.9

Especially compelling is the evidence, reported by anthropologist Donald Brown in his landmark study, Human Universals, that altruism, reciprocity, and a concern for fairness are cultural universals.10 There is also the extensive research by evolutionary psychologists Leda Cosmedes and John Tooby and a number of their colleagues on what they term “social exchange” (or reciprocity) – which they point out also exists in every culture. Cosmedes and Tooby have concluded that humans possess a discreet “mental module” -- a dedicated neurocognitive system – for reciprocity behaviors.11

In a similar vein, the work on “strong reciprocity theory” in experimental and behavioral economics has repeatedly shown that even altruistic behaviors can be elicited in cooperative situations if there is a combination of strict reciprocity and punishment for defectors.12

Finally, it has been shown that even some nonhuman primates display in a rudimentary form some of the traits associated with fairness behaviors in humans. For instance, primatologist Frans de Waal, in a classic laboratory experiment, clearly demonstrated the existence of reciprocity behaviors in capuchin monkeys.13

It seems evident that a sense of fairness is an inborn human trait. This means, quite simply, that we are inclined to take into account and accommodate to the needs and interests of others. However, it is equally clear that our sense of fairness is labile. It can be subverted by various cultural, economic and political influences, not to mention the lure of our self-interests. And, of course, there are always the “outliers” – the Bernie Madoffs.

In fact, our predisposition toward fairness, like every other biological trait, is subject to significant individual variation. Numerous studies have indicated that some 20-30 percent of us are more or less “fairness challenged.”14 Some of us are so self-absorbed and egocentric that we are totally insensitive and even hostile to the needs of others. Ebenezer Scrooge (in Charles Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol”), and the banker Henry F. Potter (in Frank Capra’s timeless Christmas movie “It’s a Wonderful Life”) were caricatures, of course, but many of us have seen likenesses in real life.

III. The Social Contract

Thus fairness is not a given. It is an end that can only be approximated with consistent effort and often in the face of strong opposition. And in the many cases where there are conflicting fairness claims, compromise is the indispensable solvent for achieving a voluntary, consensual outcome. At the individual level, fairness is an issue in all of our personal relationships -- in our families, with our loved ones, with friends, and in the workplace. We are confronted almost every day with concerns about providing, or doing, a “fair share,” or reciprocating for some kindness, or recognizing the rights of other persons, or being fairly acknowledged and rewarded for our efforts.

However, fairness is also an important, “macro-level” political issue in any society, and the debate about “social justice” can be traced back at least to Plato’s great dialogue, The Republic.15 For Plato, social justice consists of “giving every man his due” (and every woman, of course). His great student, Aristotle, characterized it as “proportionate equality.”16 Plato also advanced the idea that every society entails a social “compact” – a tacit understanding about the rights and duties, and benefits and costs, of citizenship – and he viewed social justice as the key to achieving a stable and harmonious society.

The idea that there is a more or less well-defined “social contract” in every society is more commonly associated with the so-called social contract theorists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – such as Jean Jacques Rousseau, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke – and more recently, John Rawls. Rousseau fantasized about free individuals voluntarily forming communities in which everyone was equal and all were subject to the “general will.”17 Hobbes, in contrast, envisioned a natural state of anarchic violence and proposed, for the sake of mutual self-preservation, that everyone should be subject to the absolute “sovereign” authority of the state.18 Locke, on the other hand, rejected this dark Hobbesian vision. He conjured instead a benign state of nature in which free individuals voluntarily formed a limited contract for their mutual advantage but retained various residual rights.19

The philosopher David Hume, and many others since, have made a hash of this line of reasoning. In his devastating critique, A Treatise of Human Nature (published in 1739-40), Hume rejected the claim that some deep property of the natural world (natural laws), or some aspect of our past history, could be used to justify moral precepts. Among other things, Hume pointed out that even if the origins of human societies actually conformed to such hypothetical motivations and scenarios (which we now know they did not), we have no logical obligation to accept an outdated social contract that was entered into by some remote ancestor.20

With the demise of the natural law argument, social contract theory has generally fallen into disfavor among philosophers, with the important exception of the work of John Rawls. In his 1971 book, A Theory of Justice, Rawls provoked a widespread reconsideration of what constitutes fairness and social justice and, equally important, what precepts would produce a just society.21 Rawls proposed two complementary principles: (1) equality in the enjoyment of freedom (a concept fraught with complications), and (2) affirmative action (in effect) for “the least advantaged” among us. This would be achieved by ensuring that the poor have equal opportunities and that they would receive a relatively larger share of any new wealth whenever the economic pie grows larger. Although Rawls’ work has been exhaustively debated by philosophers and others over the years, it seems to have had no discernable effect outside of academia.

However, there is one other major exception to the general decline of social contract theory that is perhaps more significant. Over the past two decades, a number of behavioral economists, game theorists, evolutionary psychologists and others have breathed new life into this venerable idea with a combination of rigorous, mathematically-based game theory models and empirical research. Especially important is the work of the mathematician-turned-economist Ken Binmore, who has sought to use game theory as a tool for resuscitating social contract theory on a new footing. In his 2005 book, Natural Justice, Binmore describes his approach as a “scientific theory of justice,” because it is based on an evolutionary/adaptive perspective, as well as the growing body of research in behavioral and experimental economics regarding our evolved sense of fairness, plus some powerful insights from game theory.22

Briefly, Binmore defines a social contract in very broad terms as any stable “coordination” of social behavior – like our conventions about which side of the road we should drive on or pedestrian traffic patterns on sidewalks. Any sustained social interaction in what Binmore refers to as “the game of life” – say a marriage, a car pool, or a bowling league -- represents a tacit social contract if it is (1) stable, (2) efficient, and (3) fair.

To achieve a stable social contract, Binmore argues, a social relationship should strive for an equilibrium condition – an approximation of a Nash equilibrium in game theory. That is, the rewards or “payoffs” for each of the players should be optimized so that no one can improve on his or her own situation without exacting a destabilizing cost from the other cooperators. Ideally, then, a social contract is self-enforcing. As Binmore explains, it needs no social “glue” to hold it together because everyone is a willing participant and nobody has a better alternative. It is like a masonry arch that requires no mortar (a simile first used by Hume).

The problem with this formulation – as Binmore recognizes -- is that it omits the radioactive core of the problem – how do you define fairness in substantive terms? As Binmore concedes, game theory “has no substantive content…It isn’t our business to say what people ought to like.” Binmore rejects the very notion that there can be any universals where fairness is concerned. “The idea of a need is particularly fuzzy,” he tells us. In other words, Binmore’s version of a social contract involves an idealization, much like Plato’s republic, or (utopian) free market capitalism, or Karl Marx’s utopian socialism. Fairness is whatever people say it is, so long as they agree.

IV. The “Biosocial Contract”

I have taken a different approach. What I call a “biosocial contract” is distinctive in that it is grounded in our growing understanding of human nature and the basic (biological) purpose of a human society. It is focused on the content of fairness, and it encompasses a set of specific normative precepts. In the game theory paradigm, the social contract is all about harmonizing our personal interactions. Well and good. But in a biosocial contract, the players include all of the stakeholders in the political community and substantive fairness is the focus.

A biosocial contract is about the rights and duties of all of the stakeholders in society, both among themselves and in relation to the “state”. It is about defining what constitutes a “fair society.” It is a normative theory, but it is built on an empirical foundation. I believe it is legitimate to do so in this case, because life itself has a built-in normative bias – a normative preference, so to speak. We share with all other living things the biological imperatives associated with survival and reproduction (our basic needs). If we do, after all, want to survive and reproduce – if this is our shared biological objective -- then certain principles of social intercourse follow as essential means to this end. In other words, a biosocial contract represents a “prudential” political road-map that ultimately depends upon mutual consent.

First and foremost, a biosocial contract requires a major shift in our social values. The deep purpose of a human society is not, after all, about achieving growth, or wealth, or material affluence, or power, or social equality, or even about the pursuit of happiness. An organized society is quintessentially a “collective survival enterprise.” Whatever may be our perceptions, aspirations, or illusions (or for that matter, whatever our station in life), the basic problem for any society is to provide for the survival and reproductive needs of its members. This entails a broad array of some fourteen basic needs domains, which are discussed in some detail in my book.

However, it is also important to recognize our differences in merit and to reward them (or punish them) accordingly. It is clear that “just deserts” are also fundamental to our sense of fairness, as the Wall Street bonus outrage illustrated. Finally, there must also be reciprocity -- an unequivocal commitment on the part of all of the participants to help support the collective survival enterprise, for no society can long exist on a diet of altruism. Altruism is a means to a larger end, not an end in itself. It is the emotional and normative basis of our safety-net.

Accordingly, the biosocial contract paradigm encompasses three distinct normative (and policy) precepts that must be bundled together and balanced in order to approximate the Platonic ideal of social justice. These precepts are as follows:

(1) Goods and services must be distributed to each according to his or her basic needs (in this, there must be equality);

(2) Surpluses beyond the provisioning of our basic needs must be distributed according to “merit” (there must also be equity);

(3) In return, each of us is obligated to contribute to the collective survival enterprise proportionately in accordance with our ability (there must be reciprocity).

The first of these precepts, equality, involves a collective obligation to provide for the common needs of all of our people. It is grounded in four empirical propositions: (1) our basic needs are increasingly well-documented; (2) although our individual needs may vary somewhat, in general they are equally shared; (3) we are dependent upon many others, and our economy as a whole, for the satisfaction of these needs; and (4) more or less severe harm will result if any of these needs are not satisfied. (All of this is discussed at length in The Fair Society.)

Although this precept may sound socialistic -- an echo of Karl Marx’s famous dictum -- it is at once far more specific and more limited.23 It is not about an equal share of the wealth. It refers to the fourteen basic biological needs domains that are detailed in my book. Our basic needs are not a vague, open-ended abstraction, nor a matter of personal preference. They constitute a concrete but ultimately limited agenda, with measurable indicators for assessing outcomes.

These fourteen basic needs domains include a number of obvious items, like adequate nutrition, fresh water, physical safety, physical and mental health, and waste elimination, as well as some items that we may take for granted like thermoregulation (which can entail many different technologies, from clothing to heating oil and air conditioning), along with adequate sleep (about one-third of our lives), mobility, and even healthy respiration, which cannot always be assured. Perhaps least obvious but most important are the requisites for the reproduction and nurturance of the next generation. In other words, our basic needs cut a very broad swath through our economy and our society.

The idea that there is a “social right” to the necessities of life is not new. It is implicit in the Golden Rule, the great moral precept that is recognized by every major religion and culture. There is also a substantial scholarly literature on the need to establish constitutional and legal protections for social/economic rights that are comparable to political rights.24 Indeed, three important formal covenants have endorsed social rights, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations (1948), the European Social Charter (1961) and the United Nations’ International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), although these documents have been widely treated as aspirational rather than legally enforceable.25

Perhaps more significant is the evidence of broad public support for the underlying principle of social rights. Numerous public opinion surveys over the years have consistently shown that people are far more willing to provide aid for the genuinely needy than neo-classical (rational choice) economic theory would lead one to believe. (Some of these surveys are cited in my book.)

Even more compelling evidence of public support for social rights, I believe, can be found in the results of an extensive series of social experiments regarding distributive justice by political scientists Norman Frohlich and Joe Oppenheimer and their colleagues, as detailed in their 1992 book Choosing Justice.26 What Frohlich and Oppenheimer set out to test was whether or not ad hoc groups of “impartial” decision-makers behind a Rawlsian “veil of ignorance” about their own personal stakes would be able to reach a consensus on how to distribute the income of a hypothetical society. Frohlich and Oppenheimer found that the experimental groups consistently opted for striking a balance between maximizing income (providing incentives and rewards for “the fruits of one’s labors,” in the authors’ words) and ensuring that there is an economic minimum for everyone (what they called a “floor constraint”). The overall results were stunning: 77.8 percent of the groups chose to assure a minimum income for basic needs.

The results of these important experiments, which have since been replicated many times, also lend strong support to the second of the three fairness precepts listed above concerning equity (or merit). How can we also be fair-minded about rewarding our many individual differences in talents, performance, and achievements? Merit, like the term fairness itself, has an elusive quality; it does not denote some absolute standard. It is relational, and context-specific, and subject to all manner of cultural norms and practices. But, in general, it implies that the rewards a person receives should be proportionate to his or her effort, or investment, or contribution, as Plato and Aristotle insisted.

However, a crucial corollary of the first two precepts is that the collective survival enterprise has always been based on mutualism and reciprocity, with altruism being limited (typically) to special circumstances under a distinct moral claim -- what could be referred to as “no-fault needs.” So, to balance the scale, a third principle must be added to the biosocial contract, one that puts it squarely at odds with the utopian socialists, and perhaps even with some modern social democrats as well. In any voluntary contractual arrangement, there is always reciprocity -- obligations or costs as well as benefits. As I noted earlier, reciprocity is a deeply rooted part of our social psychology and an indispensable mechanism for balancing our relationships with one another. Without reciprocity, the first two fairness precepts might look like nothing more than a one-way scheme for redistributing wealth.

Accordingly, these three fairness precepts – equality, equity and reciprocity – form the goal posts for a fair society, and they are the keys to achieving the objectives of voluntary consent, social harmony, and political legitimacy.

V. How Do We Measure Up?

Using these three fairness precepts as criteria, or measuring rods, how does our society measure up? The answer, in a word, is relatively poorly.

First, let us look at how well we provide for our basic needs. Once upon a time the United States had the highest standard of living in the world, with a (relatively) egalitarian distribution of income and wealth, steadily declining poverty rates, and steadily improving social and health statistics. But all of this has changed radically over the past 30 years. Today, according to the Organization for Cooperation and Development (OECD), the gap between the rich and poor in the U.S. is the widest of any of its 30 members, except for Mexico and Turkey.27

In 2010, the top one percent of income earners took home 24 percent of the total national income, while the top 10 percent received almost half (49%). The distribution of wealth (including housing but excluding cars, clothes and personal furnishings) was equally skewed, with the top one percent owning 38 percent and the top 20 percent owning 87.2 percent. The remaining 12.2 percent of the wealth was shared among the other 80 percent of us.28

One indicator of this radical change over time can be seen in CEO salaries. In 1950, Fortune 500 CEOs earned some 20 times as much as the average worker. Today that figure is 320 times as much. CEO salaries (not counting generous perks) have ballooned to an average of $11.4 million, while the real wages of workers have actually declined.29 From 1980 to 2009, the median income of male high school graduates was down 25.2 percent (from $44,000 to $32,900 in 2009 dollars). In fact, the median income of all households is down an average of seven percent since 2000, despite the “rising tide” at the top of the income scale.30

The result of this wide disparity in income and wealth is a nation marked by islands of ever-growing affluence surrounded by a spreading sea of deepening poverty. Currently, there are at least 25 million workers who are either unemployed or underemployed, and this does not count the many millions of young people who have never been employed and cannot find jobs. Moreover, 47.3 percent of those who are working earn less than $25,000 per year, close to (or below) the current official poverty line of $22,343 for a family of four. In 2011, some 50 million low-income Americans used food stamps, the vast majority being working poor, or children, or the elderly. There are also currently more than 49 million Americans without health insurance.31

Safety net programs like unemployment insurance, food stamps, and Medicaid only partially compensate for our extreme income and wealth gap, judging by key health statistics. We now rank 45th among the nations of the world in infant mortality, below such countries as Cuba, Slovenia, Greece, Portugal and the Czech Republic, and our life expectancy at birth is even worse.32 We are ranked 50th behind such unlikely places as San Marino, Monaco, Liechtenstein, and Cyprus, as well as every other developed nation.33 Significantly, there is also a difference of 4.5 years in average life expectancy between the bottom and top 10 percent of the population in relation to income, up from 2.8 years in 1980.34

We are also slipping badly in educating the next generation. Currently, less than one-third of our eighth graders are proficient in math, science and reading. We now rank 48th in the world in math education, according to the World Economic Forum, and we are in the middle among the 34 industrialized countries in science and reading test scores.35 We also rank near bottom (18th out of 25) in our percentage of high school graduates and 15th in our share of adults holding college degrees.36

Indeed, we now have a two-tiered system in which an educated, wealthy elite perpetuates itself while a vast underclass lacks the education and skills (or the money) to move up the economic escalator; we have a lower level of economic mobility than most of the major industrialized countries.37 As the New York Times’ columnist Nicholas Kristof puts it, today “poverty is destiny.” To make matters worse, our states have been relentlessly slashing public school budgets, laying off teachers, and cutting school programs, rather than making improvements. And this is in addition to cutting unemployment benefits, tax credits for earned income, and food stamp eligibility, among other things.38

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in his second inaugural address in 1936 -- in the depths of the Great Depression -- declared “I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished.” The sad reality is that his words also ring true today, and it is time for us to face up to it. As a society, we fall far short in providing for the basic needs of our people.

Neither do we measure up with respect to the second fairness criterion (and the capitalist free market ideal) of providing consistent economic rewards for merit. The bottom-line justification for capitalism has always been that the wealth it produces has been earned by the owners and is therefore deserved (merited). Moreover, it also benefits society, although it is not shared equally, of course.

Often this is true, but often enough it is not. The wealth that is generated may be unearned by any reasonable definition of the term “merit” and, in the extreme, may actually cause harm to the rest of society. It could hardly be said that Bernie Madoff deserved the wealth that he skimmed from his Ponzi scheme, or that Angelo Mozilo earned the hundreds of millions of dollars that he took home from the fraudulent mortgage activities of Countrywide Financial. Likewise, a clear distinction must be drawn between, say, the excessive salaries and perks of corporate CEOs, or the multi-million-dollar bonuses of hedge fund managers, and any reasonable standard of economic merit, especially when worker wages are being systemically reduced in many industries.

Behind the political rhetoric, and the textbook theory, our economy is also rife with what has variously been described as “crony capitalism,” “predatory capitalism,” “casino capitalism,” and such market distortions as the advantages enjoyed by entrenched power and wealth and the many “barriers to entry” for entrepreneurs and the poor.39 Venture capital support for new businesses and the anti-poverty initiatives of private philanthropic foundations only partially offset these systemic biases.

Finally, we are also deficient with respect to the reciprocity criterion. A clear implication of this fairness precept is that we are obliged to contribute a proportionate share to the collective survival enterprise in return for the benefits we receive. This applies to the rich and the poor alike – to both wealthy matrons and welfare mothers. We have a duty to reciprocate for the benefits that our society provides. Otherwise, we are in effect free-riders on the efforts of others; we turn them into involuntary altruists. This is one reason why, for example, the issue of “workfare” – work requirements for public welfare recipients – was an issue back in the 1990s and why the passage of welfare reform legislation that mandated a work requirement for welfare beneficiaries defused this contentious issue, even though it caused some new problems (like providing adequate child care services to the poor).

However, a more serious violation of the principle of paying a fair share can be found in our dysfunctional tax system. It is riddled with inequities – from oil depletion allowances to subsidies for wealthy farmers, and greatly reduced “carried interest” tax rates for investment bankers, along with the generally regressive nature of many of our taxes that impose a relatively heavier burden on the middle class and the poor.

Even our federal income tax structure has become much less progressive over time. In 1950, when the American economy was booming, the top marginal tax rate was 91 percent on incomes over $1.68 million (in 1950 dollars). As recently as 1980, the top rate was 70 percent. In the 1990s it was lowered to 39.6 percent. Then, in the 2000s under President Bush, the rate was further reduced to 35 percent. Moreover, the tax rate on capital gains, which represent a significant share of the income of wealthy Americans, has recently been pegged at a flat 15 percent.40

Thus, according to the Tax Policy Center of the Brookings Institution, in 2011 the overall tax burden for the top one percent of taxpayers was 30 percent, while the bottom 99 percent of taxpayers had only a slightly lower rate (27.9 percent). In fact, about 46 percent of all “taxable units” paid no taxes at all, half of them due to various “loopholes” and “earmarks.”41 And this says nothing about the proliferation of offshore tax havens that have sheltered many billions of dollars from income taxes altogether.

In sum, we fall far short of what is required to achieve a fair society. It is time to re-write our social contract.

VI. Toward a New Social Contract

What would a fair society look like? Is this an unattainable ideal? In fact, it would not be so very different from some of the European "welfare capitalist" societies. (The current European currency/debt crisis will hopefully be fixed in due course.) Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, even Germany have achieved a better balance between the three key fairness principles: equality (providing for the basic needs of everyone), equity (rewarding merit and not subsidizing undeserved wealth), and reciprocity (a more balanced system of taxes and public service). None of these European countries is perfect, but collectively they provide a model for what is possible. Indeed, even our next door neighbor, Canada, puts us to shame.

Steven Hill’s recent book, Europe’s Promise, goes far toward “correcting the record” about Europe for Americans.42 He calls it the “European Way.” Despite its current financial travails, the European Way has been very successful over the past 50 years and puts into stark relief our own failings as a society. It is a stinging indictment of the things we could have done much better if we had made the right choices. Here are just a few bullet points about Europe that many Americans do not know:

- The 27 member E.U., with a population of 500 million (two-thirds larger than the U.S.) is now the world’s largest trading block, almost as large as the U.S. and China combined.

- Europe’s business sector is overwhelmingly capitalist, with many more Fortune 500 companies than the U.S. (179 versus 140). Half of the worlds 60 largest companies are European, and Europe accounts for more than 75 percent of all foreign investment in this country.

- Europe has the second largest military, with more “boots on the ground” than the U.S. and a global peace-keeping role that rivals our own.

- Europe has taken a decisive lead in “green design,” increasing energy efficiency, developing renewable energy systems and cutting back on greenhouse gasses. Europe has had a cap-and-trade system in place since 2005. Similar legislation in this country failed again in the current session of Congress.

- Contrary to the conventional wisdom, European taxes are not a crushing burden compared to those in America. Counting Social Security and Medicare taxes, along with our state and local taxes and such hidden levies as gasoline and telephone taxes, our tax burden is very close to the rate in, say, the Netherlands, at 52 percent. And if you add to that our much higher out-of-pocket costs for many services that European countries subsidize, from health care to education, child care, elder care, transportation and sick leave, we actually fare much worse.

The most distinctive feature of the European Way is its all-inclusive, cradle-to-the-grave economic security and social welfare program. Imagine a country in which there is a high level of job security, with very generous unemployment benefits and free job retraining that is immediately available, a country where, if you get sick, there is paid sick leave and low cost or even free health services, where higher education is free or very low cost, where child care services are readily available at low cost, or even free, and are provided by skilled professionals, where new parents are paid to stay at home and care for newborns and even receive payments to help defray the cost of diapers, extra food, etc., where workers receive two months of vacation each year, as well as generous retirement benefits and low-cost elder and nursing care. As Hill says in his book: “To most Americans, such a place sounds like Never, Never Land. But to most Europeans…America is the outlier.”

What can be done to reform our own dysfunctional society? First, we need to undertake a national full employment program that is committed to providing productive jobs for everyone who is able to work, and with a "living wage," not our delusional minimum wage. (This would further all three fairness precepts at once.) It would, of course, require a sustained, multi-faceted effort, including a public-private partnership. There are a many areas where adding more jobs would be socially productive, from re-hiring laid off teachers, fire fighters, and health care workers to construction workers for badly needed infrastructure improvements (decrepit roads, bridges, dams, sewers, etc.) and the technicians needed to help develop leading-edge technologies.

Beyond this, we must progressively increase our minimum wage to a more realistic level. (The State of Washington currently leads the way among the states with a state-wide minimum wage of just over $9 per hour.) Some theorists believe a gradual minimum wage increase to $15 per hour (with some targeted exceptions) would be justified. This would go far toward ensuring that everyone’s basic needs are provided for without handouts. Moreover, the benefits would be earned and would be consistent with the equity (merit) precept.

Equally important, we must greatly strengthen the “safety net" for the many people in our society who cannot work, including the extreme old, the very young, and those with various "no-fault" needs, like those who are severely disabled and sick. Improvements to public services like transportation and especially education are also imperatives, along with repairing our deteriorating infrastructure. A commitment to providing for the basic needs of all our citizens is affordable even as we are paying down our national debt, if there were the political will to do so, by selectively increasing taxes and eliminating tax loopholes. (There is much more on this in my book.)

Our capitalist system also needs to be reformed in order to align it more closely with merit (equity). The model going forward should be "stakeholder capitalism."43 As the term implies, this is a kind of capitalism in which all of the stakeholders are empowered and can influence the way a business operates -- the workers, the customers, the community, the suppliers, even government (mostly through regulations and incentives), not just the owners and shareholders who predominate in our form of capitalism. It changes the balance of power and, as a result, the operative values of capitalist enterprises. Examples of companies that practice stakeholder capitalism can be found even now in our society. I describe one, the farmer-owned Organic Valley food company, in the book, and there are many more examples both here and in other countries.

To balance the benefits with a comparable obligation for reciprocity, there needs to be a top-to-bottom reform of our corrupt tax system. Yes, the rich will end up paying more (their fair share), but there will also be an end to the cornucopia of tax breaks, and subsidies, and loopholes, and dubious incentives. And yes, we also have to "fix" Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, but not with "reforms" that are in fact a hidden agenda for privatizing and destroying these programs. Beyond this, the long-simmering idea of a broad, national public service program that asks everyone to give back to our society with their time and talents could have a transformative cultural influence.

Finally, to achieve all this we need major structural reforms in our broken political system -- eliminating the filibuster rule in the Senate; reducing the power of money in our politics; reforms to our election campaign financing system; non-partisan redistricting to eliminate Gerrymandering; restrictions on the “revolving door” between government and the private sector, and more.

This is, of course, only a sketch. There are many more, perhaps even better ideas out there for what could be done to affect a major course change in our society. But none of this can be accomplished without visionary and inspiring leadership and a powerful wave of public support. What is needed going forward is an "Occupy Washington" movement armed with the demand for a "Fair Society" -- a sweeping reform platform that could win a clear electoral mandate for the necessary changes. Such reforms have happened before in our history, with anti-trust legislation, the minimum wage, collective bargaining rights for workers, Social Security and Medicare, civil rights, women’s rights, accommodations for Americans with disabilities, and more.

In short, there are numerous precedents for positive changes, and there is every reason to believe that it can happen again. Political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson point out in their 2010 book, Winner-Take-All Politics, it was politics that got us into this mess and politics can get us out of it.44 But we are the only ones who can make it happen. As the TV host and commentator Bill Moyers put it: “The only answer to organized money is organized people.” The ball is in our court.

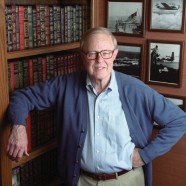

Peter Corning is the Director of the Institute for the Study of Complex Systems. Also a one-time science writer for Newsweek and professor in Human Biology at Stanford University, and the author of several previous books, including The Synergism Hypothesis: A Theory of Progressive Evolution (1983), Nature’s Magic: Synergy in Evolution and the Fate of Humankind (2003) and Holistic Darwinism: Synergy, Cybernetics and the Bioeconomics of Evolution (2005). This article is drawn from his 2011 book, The Fair Society: The Science of Human Nature and the Fate of Humankind.

1 See www.nytimes.com/2009/01/29/business/29bonus.html.

2 For net worth decline, see http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123687371369308675.html Also, http://www.usatoday.com/money/perfi/credit/2011-03-24-recession-hurts-americans-net-worth.htm For job losses, see http://www.usnews.com/opinion/mzuckerman/articles/2011/02/11/the-great-jobs-recession-goes-on. For details about the bank bailout package, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_Economic_Stabilization_Act_of_2008.

4 See http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/19/us/census-measures-those-not-quite-in-poverty-but-struggling.html?pagewanted=all Also, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/14/us/14census.html?pagewanted=all

5 The Fair Society: The Science of Human Nature and the Pursuit of Social Justice (University of Chicago Press, 2011).

6 See especially J. Philippe Rushton, David W. Fulker, Michael C. Neal, David K.B. Nias, & Hans J. Eysenck. Altruism and Aggression: The Heritability of Individual Differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50: 1192-1198 (1986). Also, see Thomas J. Bouchard, Genetic Influence on Human Psychological Traits. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13(4): 148-151 (2004).

7 See http://sciencedaily.com/releases/2001/09/010914074303.htm

8 Alan G. Sanfey, Social Decision-making: Insights from Game Theory and Neuroscience. Science 318: 598-602 (2007).

9 See the overview and references at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_J._Zak

10 Donald E. Brown, Human Universals. (Temple University Press, 1991).

11 See their overview chapter in David M. Buss, ed. The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. 584-626 (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

12 See eg., Herbert Gintis, Punishment and Cooperation. Science 319: 1345-1346 (2008). Also Herbert Gintis, Samuel Bowles, Robert Boyd, and Ernst Fehr, eds. Moral Sentiments and Material Interests: The Foundations of Cooperation in Economic Life. (The MIT Press, 2005); Herbert Gintis & Ernst Fehr, Human Nature and Social Cooperation. Annual Review of Sociology 33(3): 1-22 (2007).

13 Described in Jessica Flack & Frans B.M. de Waal, Any Animal

Whatever: Darwinian Building Blocks of Morality in Monkeys and Apes. Journal of

Consciousness Studies 7(1-2): 1-29 (2005).

14 Supra note 5, 155-156. See also Samuel Bowles & Herbert Gintis, Is Equality Passé?: Homo Reciprocans and the Future of Egalitarian Politics. Boston Review (Fall): 4-10 (1998). This is also a consistent finding in the research on strong reciprocity theory, supra note 12.

15 Plato, The Republic. Trans. B. Jowett. (World Publishing Company, 1946/380 B.C).

16 Aristotle,

Nichomachean Ethics. Trans. Terence Irwin. (Hackett, 1985/350 B.C.).

17 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Of the Social Contract. Trans. Charles M. Sherover. (Harper & Row, 1984/1762).

18 Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan: On the Matter Form and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil. (Collier Books, 1962/1651).

19 John L. Locke, Two Treatises of Government. Ed. P. Laslett. (Harvard University Press, 1970/1690).

20 David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature. 2nd ed. Ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge. (Clarendon Press, 1978/1739).

21 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice. (Belknap Press, 1971).

22 Ken Binmore, Natural Justice. (The MIT Press, 2005).

23 Equality has been a socialist and liberal/progressive ideal ever since the Enlightenment. See especially Michael J. Sandel, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009). Many theorists have focused on equality in terms of human rights, economic opportunities, or due process of law. However, economic egalitarians, beginning with Rousseau (supra note 17), have stressed an egalitarian distribution of the wealth and property of a society. From the perspective of the three fairness precepts associated with the biosocial contract paradigm, the radical socialist ideal is misguided. Or, better said, it must be strictly limited to the domain in which we are indeed equal – our basic needs. This leaves ample room for differentially rewarding our inequalities in talent, efforts and achievements. (The shortcomings of socialism are discussed in some detail in my book.)

24 See eg., Cécile Fabre, Social Rights Under the Constitution: Government and the Decent Life. (Oxford University Press, 2000). The abstract for the book notes that “The desirability, or lack thereof, of bills of rights has been the focus of some of the most enduring political debates over the last two centuries. Unlike civil and political rights, social rights to the meeting of needs, standard rights to adequate minimum income, education, housing, and health care are usually not given constitutional protection. The book argues that individuals have social rights to adequate minimum income, housing, health care, and education, and that those rights must be entrenched in the constitution of a democratic state. That is, the democratic majority should not be able to repeal them, and certain institutions (for instance, the judiciary) should be given the power to strike down laws passed by the legislature that are in breach of those rights. Thus, the book is located at the crossroads of two major issues of contemporary political philosophy, to wit, the issue of democracy and the issue of distributive justice.”

25 The Universal Declaration included social (or “welfare”) rights that address matters such as education, food, and employment, though their inclusion has been the source of much controversy. See eg., D. Beetham What Future for Economic and Social Rights? Political Studies, 43: 41–60 (1995). The European Social Charter treaty, enacted by the Council of Europe in 1961, also guaranteed economic and social rights. See http://www.coe.int/T/DGHL/Monitoring/SocialCharter/ Article 1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted by the General Assembly in 1966 and entered into force ten years later, in January of 1976, declared in part: “In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.” See http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cescr.htm The list of specific rights in the Covenant includes nondiscrimination and equality for women in the economic and social area (Articles 2 and 3), freedom to work and opportunities to work (Article 4), fair pay and decent conditions of work (Article 7), the right to form trade unions and to strike (Article 8), social security (Article 9), special protections for mothers and children (Article 10), the right to adequate food, clothing, and housing (Article 11), the right to basic health services (Article 12), the right to education (Article 13), and the right to participate in cultural life and scientific progress (Article 15). For a more detailed discussion of social rights, see Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rights-human/#EcoSocRig

26 Norman Frohlich, & Joe A. Oppenheimer. Choosing Justice: An Experimental Approach to Ethical Theory. (University of California Press, 1992).

27http://www.oecd.org/document/40/0,3746,en_21571361_44315115_49166760_1_1_1_1,00.html

28 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Income_inequality_in_the_United_States Also http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/cwed/wp/wealth_in_the_us.pdf

29 http://www.aflcio.org/corporatewatch/paywatch/ceou/database.cfm

30 http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=77 Also http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/story/2011-09-13/census-household-income/50383882/1

31 See The Fair Society, supra note 5, 115-117.

32 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2091rank.html

33 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2102rank.html

34 “Snapshot for July 16, 2008. Growing Disparities in Life Expectancy” Elise Gould Economic Policy Institute, http://www.epi.org/economic_snapshots/entry/webfeatures_snapshots_20080716/

35 World Economic Forum, The Global Competitiveness Report 2011-2012, http://www.weforum.org/reports/global-competitiveness-report-2011-2012

37 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/03/17/social-immobility-climbin_n_501788.html

38 http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=1214

39 See especially James K. Galbraith, The Predator State: How Conservatives Abandoned the Free Market and Why Liberals Should Too. (Free Press, 2008); Joseph E. Stiglitz, Freefall: America, Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. (W.W. Norton, 2010); The Fair Society, supra note 5.

40 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=213

41 The remaining half had incomes that fell below the minimum tax threshold. Why Some Tax Units Pay No Taxes, Rachel M. Johnson et. al., July 27, 2011

www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1001547; www.ctj.org/pdf/taxday2011.pdf

42 Steven Hill, Europe's Promise: Why the European Way is the Best Hope in an Insecure Age. (University of California Press, 2010).

43 See especially Gavin Kelly, Dominic Kelly, and Andrew Gamble, eds., Stakeholder Capitalism. (St. Martins Press, 1997).

44 Jacob S. Hacker & Paul Pierson, Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer – And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. (Simon & Schuster, 2010).